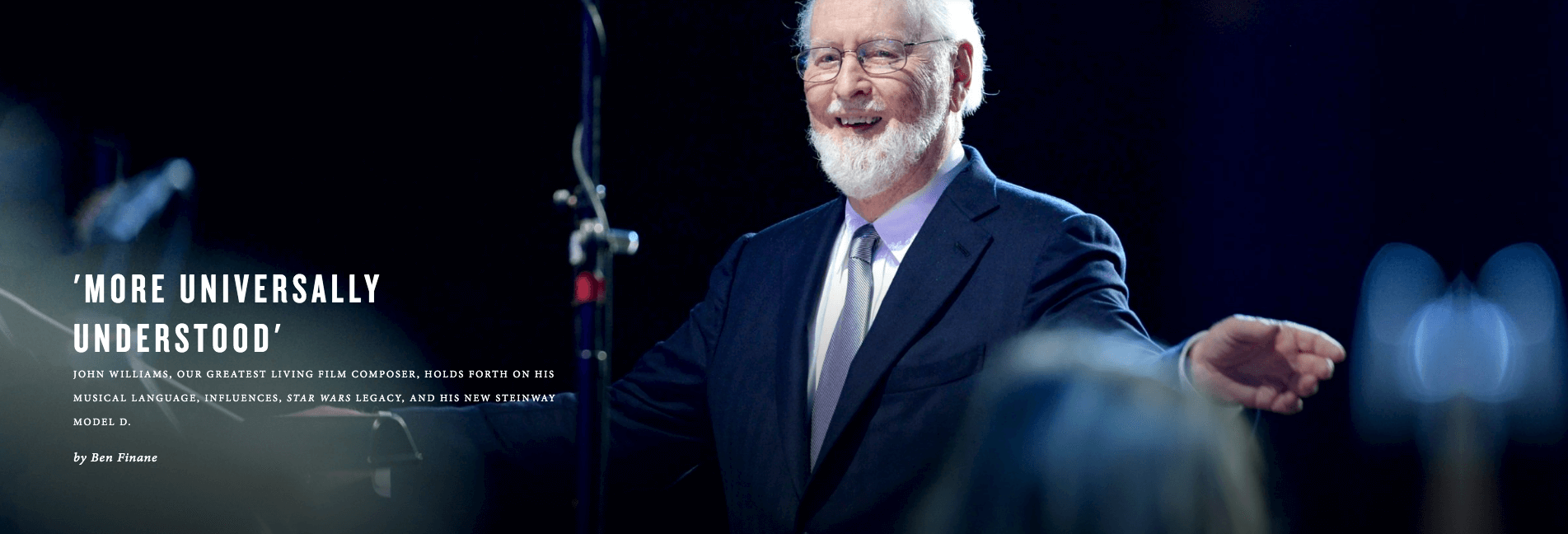

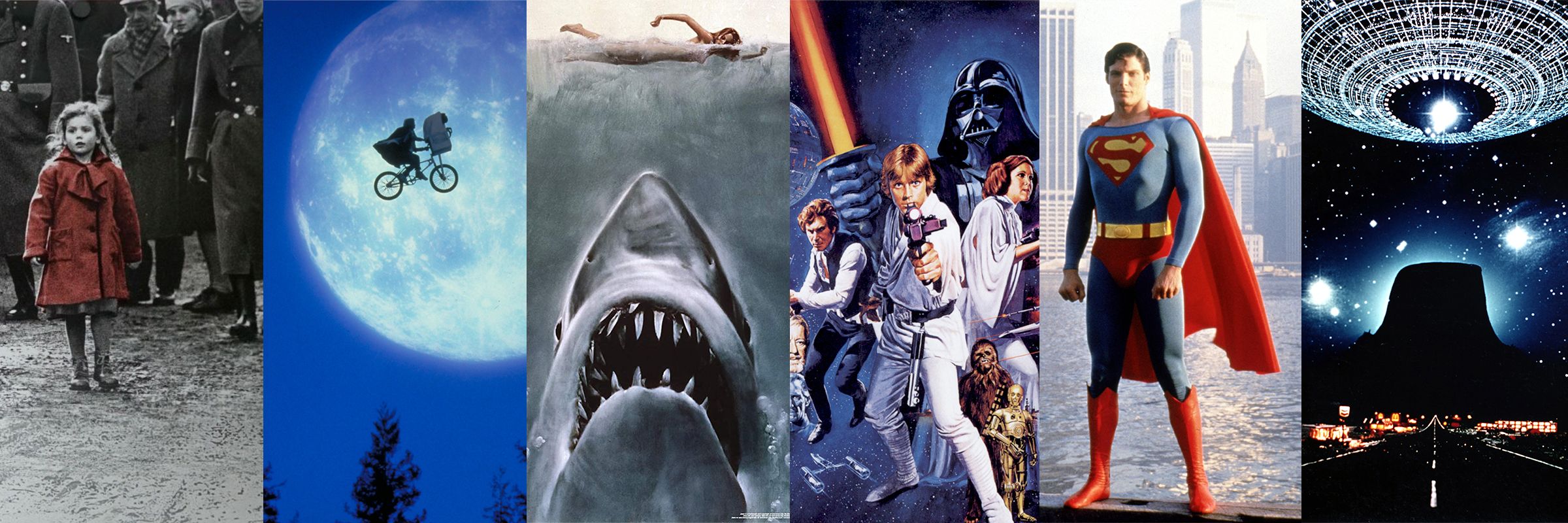

Star Wars, Superman, E.T., Indiana Jones, Jaws, Schindler’s List, Close Encounters of the Third Kind: John Williams defined the sound of contemporary cinema. The affable and articulate composer spoke from his home in Los Angeles with Steinway & Sons Editor in Chief Ben Finane in a wide-ranging conversation on music, influence, craft, and Steinways.

Thank you for speaking with me, Mr. Williams. My daughter is now seven years old and she was into Superman for a while, at the age of four. So I told her, “Did you know Superman has his own music?” And she says “No!” She says, “Please play it for me.” So I play it, I play your theme. And in the intro, when we have this [sings the string ostinato intro], she turns to me and she says, “He’s coming — Superman is coming!” So I found that really fascinating, because that’s universality: I didn’t have to explain to her that you were building musical tension and that you were adding the fourth and fifth, et cetera. She understood that those strings meant that Superman was on his way, intuitively. And so I think the universality of your language is real. And I’m wondering if we could talk about what goes into that language.

I love that about your daughter — that’s wonderful. Well I suppose the subject of universality raises all kinds of social and cultural questions. It’s interesting to me that in China, I’m told they’re buying more pianos than in any other country these days. So even with their own rich musical vocabulary and performance traditions, they seem to be as much in love with Beethoven as we are. There may be some cross-cultural aspects of the use of tonality. Beethoven, of course, was a product of a three- or four-hundred-year history of church music and other European music, and particularly North German contrapuntal development over the years seems to have touched on something in the overtone series that is, in fact, universal. In this way, the Chinese may be more receptive to North German counterpoint than we are to the complexities in their indigenous music which, as I understand it, is not written down at all, but is passed on orally and from master to apprentice. Leonard Bernstein, in his wonderful Norton Lectures, had so much to say about this question you’ve posed. I don’t think I have any particular answers for it, but it’s very exciting to me that music seems to be more universally understood than so many of the other gifts we’ve been given.

Well, let’s switch gears from Beethoven. I played piano first, but I sure played a lot of drums in John Williams medleys, both in concert and marching band, growing up. In your formative years, what did you learn working as a session musician under Henry Mancini? What did you learn from Bernard Herrmann?

I learned a lot from them both, probably through some process of absorption I suppose. In the case of Henry Mancini, he was a very practical musician. A composer of Gebrauchsmusik would be a word that might apply in his case. He wrote very simple music but it was particularly suited to films. His scores are very economical and very effective. In the case of Herrmann, he used to say to me, “use a pen when you orchestrate… you’ll think before you write the notes.” And for some years I did actually orchestrate only in pen, not because Benny suggested that I do it, but because the scores looked much better than the pencil ones. The thing about Herrmann was that he was a forceful personality and that force in his personality found its voice in those hammering, repetitive themes of his, which you can’t get out of your ear. He was a fascinating personality and, in many ways, an important musician. Although extremely conservative even in his early days in the 1930s, he conducted the American premieres of some of Schoenberg’s works at CBS, as you may know. Anyway, I enjoyed both of them more as friends than anything else. I was grateful for the opportunity to meet them and to befriend them through the many years that followed.

‘It’s very exciting to me that music seems to be more universally understood than so many of the other gifts we’ve been given.’

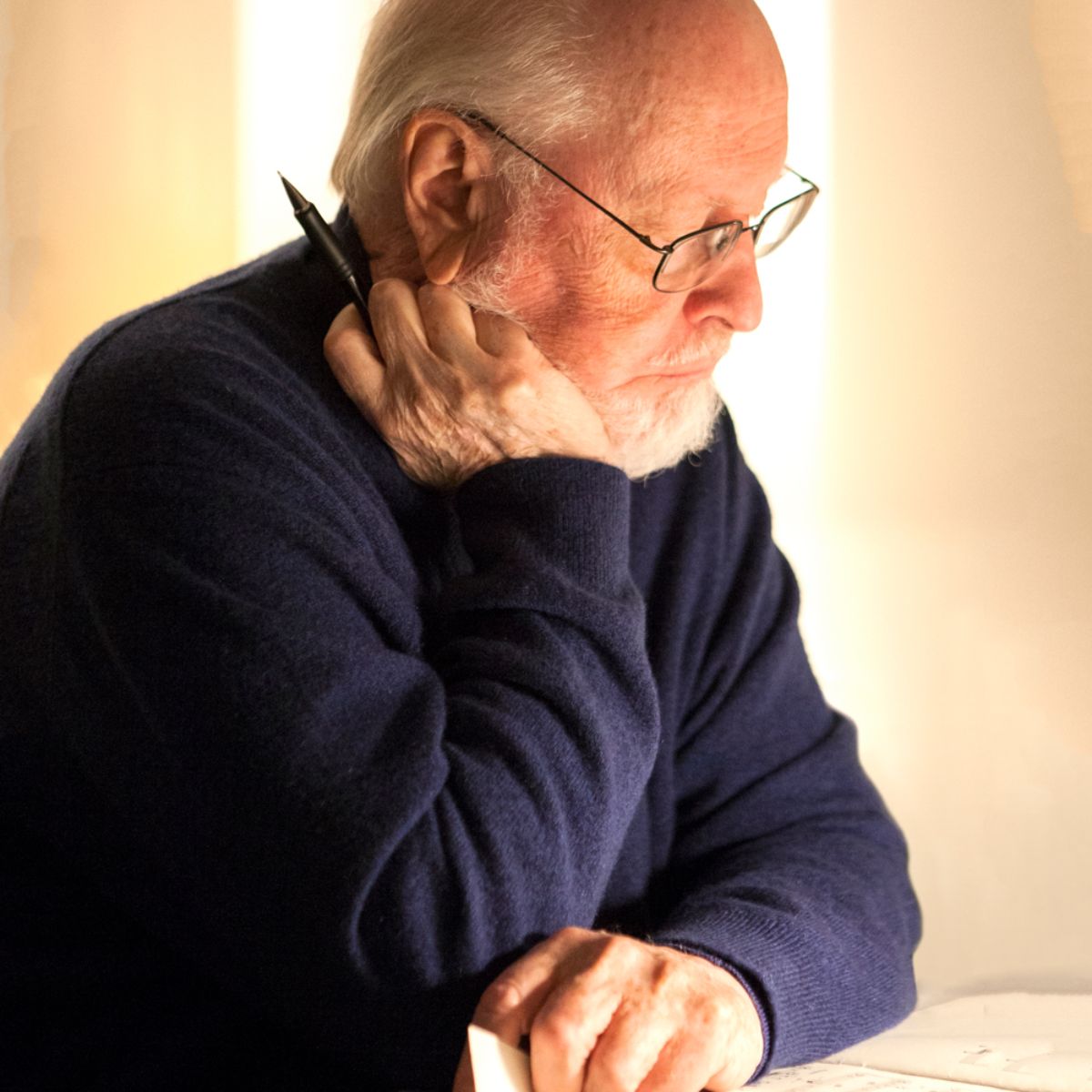

Do you still compose with a pen? Have you made the shift to a—

Oh no, I’m not shifting. While composing, I’m scribbling with a pen and throwing pages all over the room and it’s very, very primitive. Then I use… what I do is write a 10 or 12 line sketch, which works very well, and they can extract the parts and score from that. It really doesn’t need orchestration. The only time you get into trouble with that is if there’s a lot of percussion or two harps or two harps and a piano, you need a lot of lines for that. So I’ve developed a way to tape those together if the short score is not long enough. But that’s really pretty rare in the kind of work that we do. In films, either it’s a smaller orchestra or, in the case of Star Wars, it’s straightforward, from an orchestration point of view, it’s triple winds and five horns and the usual brass. There’s nothing about it that that’s particularly exotic from an instrumentation point of view. I don’t use any electronics on those scores, in part because I think the idea originally was to make scores as Romantic and late-nineteenth-century, in texture and style, as we could.

Do you feel that’s still your core aesthetic, late-nineteenth-century Romanticism brought to present day?

While It’s been very useful in my commercial work, my concert works have been very different, more in the direction that I might’ve gone if I hadn’t done so much commercial work. For example, I’m writing a concerto for Anne-Sophie Mutter at the moment, which will premiere next summer at Tanglewood.

It’s great that you can keep a foot in both worlds.

Well, it’s almost a required mental exercise for me. And I suppose the one discipline is a source of inspiration and energy for the other.

I know that every movie is different. Are there things that you absolutely do every time, when you’re writing a film score? Are there elements in a process that you stick to?

No. The scores can be as different as Star Wars is from Images or Schindler’s List is from Indiana Jones. When I look at films with directors, I’m always asking myself the question, “What should this film sound like? What should Superman’s music be if we didn’t have it?” And so, I really approach each one as a very individual case.

“When I look at films with directors, I’m always asking myself the question, ‘What should this film sound like? What should Superman’s music be if we didn’t have it?’”

Do you write at the Steinway?

Yes, I do. I write at the piano every day. Actually, I have three wonderful Steinways. The one I’ve had the longest is a 1969 Hamburg Steinway Model C. And then one that I have at my studio is a Model B acquired in the early 2000s. It’s a wonderful piano. The new one that I’ve just gotten is the Model D.

The Model D is our biggest concert grand. Why did you get the new Steinway?

Well, for the joy and fun that it brings me every day. I thought it would be really inspirational to have a new voice in my musical life because I live with the piano and use it so much. So, I went down to my local Steinway gallery and played some of them, and I quite fell in love with this one. And I’ve enjoyed it greatly every day. It’s a masterpiece of form and function, and also a very beautiful work of sculpture. Like nothing other than perhaps a Stradivarius violin, which could be described in the same way. You think about the kind of fortissimos possible on these pianos, which can be imbued with such power and force, and in the same measure can be transformed into a wafting pianissimo. It seems to me to be an incredible feat of engineering that something mechanically can be so responsive to a very heavy hand, and yet seconds later, respond so beautifully to that same hand, if it’s skilled enough, conjuring the gentlest sounds… revealing their beauty and then wafting away almost instantly. This magnificent instrument is a new friend for me and I am enjoying it tremendously. And I feel very, very fortunate to have the use of it while I’m here.